Despite its highest protection status in Indonesia, orangutans are not well protected from crime. Forest clearing to make way for oil palm plantations, mining, agriculture, logging concessions and population expansion has created the greatest threat to the survival of the orangutan. Habitat destruction has decimated orangutan populations over the last decade. The Orangutan Project funds numerous orangutan rescue teams in Sumatra and Borneo that are highly trained and skilled at relocating wild orangutans in high-risk situations into protected forest habitat.

Land clearing creates a myriad of other threats including poaching, illegal possession and the black-market trade. These rescue teams also undertake confiscations of illegally held ‘pet’ orangutans. Sadly, many infant orangutans are kept and sold illegally as pets in Indonesia. This occurs when the mother has been killed – usually because they are considered an ‘agricultural pest’ if they enter oil palm plantations to find food, since so much of their natural habitat and food sources have been destroyed. Infant orangutans are highly traumatised after witnessing the brutal killing of their mothers who they would have been highly dependent on for many years. They are then often kept in deplorable conditions as someone’s pet and fed inappropriate food.

Once these young orangutans are confiscated by rescue teams, they are taken to the appropriate care centre depending on which area they originated from. Here they undergo a full medical check and are treated for any illnesses and parasites. New arrivals undergo a quarantine period before being introduced to other compatible orangutans. It is imperative that orangutans at these care centres are provided with enrichment to keep them mentally and physically stimulated. Orangutans are highly intelligent and spend most of their day in the forest traveling and searching for food. If orangutans are confined and bored this can result in stereotypic and negative behaviours including pacing, hair plucking, rocking and regurgitation of food.

One of the biggest problems faced when reintroducing orangutans to the wild that have spent considerable time in captivity is their inability to be able to recognise available food sources, especially during seasonal variations. Wild orangutans eat hundreds of different plant species and they change their diet according to the season and food availability to survive. Orangutans predominantly feed on high calorie fruits during the fruiting season but must rely on eating other food sources such as leaves, termites and cambium when fruit is scarce.

Young orangutans at the care centres and training release sites are taken out for ‘forest school’ outings where they can develop the skills that they need to survive in the wild including nest building, travelling in the forest canopy and identifying natural food sources. They would normally take years to learn these skills from their mother in the forest, so the rehabilitation journey is a slow process. Orangutans develop at different rates depending on their age, temperament and how long they spent with their mother in the forest.

Orangutans are observed closely during forest school by orangutan trainers and their activity patterns of travelling, foraging and resting are closely monitored and recorded. Orangutan trainers also closely observe and record what foods the orangutans are eating. It is very important that orangutans learn to mostly eat fruit during the fruiting season to increase their calorie intake and fat reserves to help them survive during the dry season. Orangutans must also be able to recognise and eat a wide range of other forest foods including flowers, termites, bark and cambium. Young orangutans need to learn how to make a strong and stable nest in the canopy. This can often take a long time to learn since it is quite a complex procedure. Often young orangutans watch and learn how to build nests from other more experienced orangutans at forest school. It is also vital that young orangutans do not come to the ground, especially in Sumatra, since the Sumatran tiger is a natural predator.

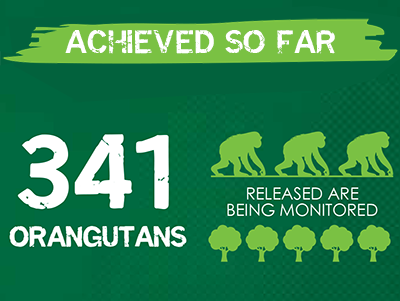

Even after release, orangutans are closely monitored to ensure they are adapting to full-time jungle life. Orangutans at some release sites have a small transponder inserted between their shoulder blades so they can be tracked using telemetry equipment well after their release to check on their progress. This has been a huge development in allowing longer term monitoring and assessment of released orangutans. It also allows the orangutans trainers to reduce the monitoring of the orangutan over time as they adapt to their environment. The Orangutan Project supports the post-release monitoring of orangutans at numerous sites in both Borneo and Sumatra.

The Orangutan Project funds the rescue, rehabilitation and release of orangutans through the following projects: